Edwards Ham

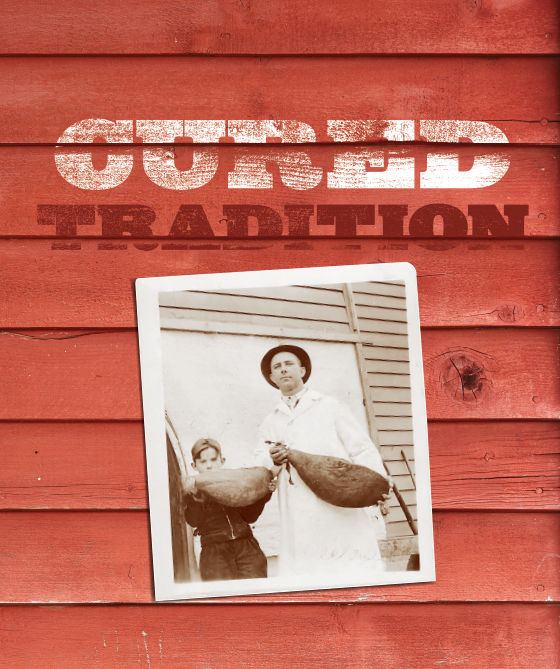

From the spark of an idea, the Edwards family has built a legacy of taste.

photography by Adam Ewing

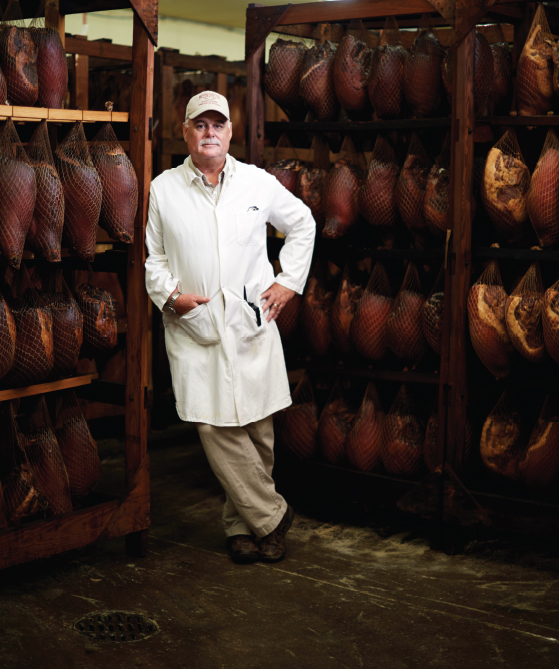

SURRY – Sam Wallace Edwards III pulls open the doors and thick gray smoke smelling of hickory and ham rolls out like a fog. His father built this business, and his grandfather before him, and Sam has known since he was a boy how to stick an ice pick into a piece of smoked meat, sniff it and tell whether that meat is ready for someone’s table.

He can look at the color of a slab of bacon and tell if it has had enough time in the smoker, and at a piece of raw meat and tell you whether it came from a commodity pig or a pasture-raised heritage breed. He has swept the floors, split the wood and hefted heavy hams from bin to table to rack. In a family business there is no minimum wage, there are no child labor laws. There’s love and there’s work and there’s ham.

The story of ham in America began 400 years ago, just across the river, when Jamestown settlers unloaded cargo loads of pigs that rooted and ran and rutted, feeding on acorns and hickory nuts and reproducing in such numbers that they became a nuisance. So the settlers herded them back onto boats, this time to head a mile downstream to what is now called Hog Island, where they became an easily caught source of protein.

The colonists’ Native American neighbors had long before developed a way to preserve venison, and they taught them the secrets of salt and smoke. Together they would slaughter the animals in the fall, wash them and rub them down with salt, smoke them, then let them age through the winter and into the spring, allowing the salt and the changes in temperature to turn raw muscle into bacon and ham.

Jamestown rose and faded. So did neighboring Williamsburg.

But Williamsburg rose again. In 1925, Colonial Williamsburg had just opened and tourists were streaming across the James River, 16 Model T’s per load, on the ferryboat Capt. John Smith, owned by the entrepreneur Albert F. Jester and piloted by his bowler-wearing son-in-law, Sam Wallace Edwards Sr.

Wallace, as he was known, had grown up on a farm, raising peanuts and pigs and processing the animals in his backyard smokehouse into bacon and ham. In those days the pigs wandered the peanut fields, gorging on goobers the harvesters had left behind. The peanuts made the pigs’ meat rich and fatty, and it matured into juicy, delicious hams. One day during the choppy 2¾-mile river crossing it occurred to Wallace that perhaps he could combine his jobs and make extra money selling food to his passengers.

Soon his bread-baking, ham-cooking wife, Oneita, was sending him off each morning with a boxful of sandwiches wrapped in butcher paper. Word spread and within a year he was selling whole hams to restaurants and country stores, and through a mail-order catalog. That first year they processed 55 hams.

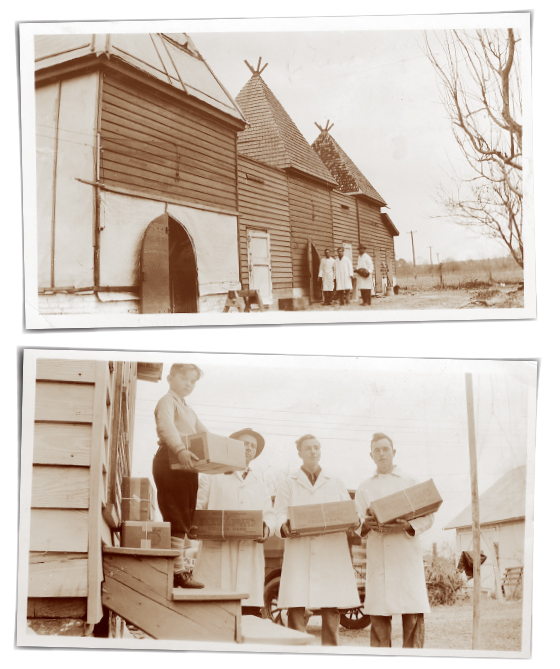

Over the next decade Edwards built another smokehouse, then another, adding 500 square feet here and 1,000 there, creating what his grandson calls a hodgepodge of rooms as the need arose. The smokehouses had roofs shaped like teepees as an homage to the American Indians who had kept the settlers alive. On each roof he painted a letter –

H. A. M. – visible to Route 31, the road tourists took coming down from Richmond and other parts north.

The original smokehouses, like the Wigwam brand, honored the people who helped the European settlers survive. Deliveries for the holidays: Wallace Jr., left, and his dad, at far right.

Edwards added a ham kitchen onto the back of the house, with a concrete floor with a drain in it and a stove big enough that Oneita could cook four at a time – two per giant pot. During the 1920s and ’30s she’d cook between 100 and 150 hams for the Christmas rush, paint each with a brown sugar-and-clove glaze, wrap it in cellophane, put it in a box and top it with a sprig of holly with berries that her husband had gathered from the woods. They called them Wigwam hams, and the boxes carried an etching of a teepee with smoke drifting from its peak.

In 1940, the Edwardses built a slaughterhouse just outside Surry – in the suburbs, as Sam likes to say. They used trailers with corrugated metal sides and roofs and a canvas curtain across the back to carry racks of carcasses, rattling and rocking as tractors pulled them through town to a cutting room, where men in white aprons and street hats carved them into hams and hocks and bellies.

It is the alchemy of salt and temperature and time that breaks down pig muscle proteins into bacon and ham, like a grape turning to a raisin or its juice turning to wine. The longer each is cured, the more intense the flavor.

But working with the seasons was limiting and unpredictable, so Edwards brought the process inside, designing rooms that mimicked optimal outdoor temperatures. The aging, though, still occurred at whatever temperature and humidity Mother Nature delivered. When Wallace Jr. took over in the late ’60s he studied which year produced the best hams, then created an aging room that duplicated that weather.

Young Sam watched and learned. He saw his grandfather use a blue crayon to put a check mark on the hams he thought were the best. These he’d pull out for family holidays, or the weddings and special occasions of customers and friends. He watched his father, too.

“Dad always said we’re always learning little things about what we can do to make it better, from the raw materials, to the wood, to the times and temperatures you have to adjust, because Mother Nature always throws you a curve,” Sam says. “You’re not just applying step one, two and three, you’re using your sense of touch, taste and smell to make decisions about tweaking that process.”

One day as a teen, young Sam was shoveling effluent out of the room-sized grease trap. His father didn’t believe in hiring septic tank cleaners to suck out the grease. “He believed in us shoveling it into barrels and letting the tallow company pay us for it,” says Sam, “like, a penny a pound.”

So Sam balanced a 2-by-6 across the trap, bent over and shoveled grease into barrels. It was hot, and some of the grease dripped onto the board. Sam stepped into it, slipped and fell into 6 feet of August-hot pig grease.

“I took about 17 showers and still couldn’t get that off of me,” he says now.

He told his dad he’d rather pay the septic fee himself than have anyone there shovel grease.

“Dad said, ‘Yeah, but that cost us 50 bucks and you’re only getting 50 cents an hour. Do the math, son.’ ” To which Sam countered, “I coulda drowned.”

It took the septic company half an hour to clean out the pit, and it’s now a job Sam’s own children and employees never have to do.

Sam went away to the University of Richmond, earned a degree in business, and at age 22 came back and begged his 48-year-old dad to turn over the keys. Now, at 58, he drives the four miles from his home on the river, right next to the dock for the ferry once piloted by his grandfather. He arrives at 6:30 in the morning and “works just 12 hours,” as he says. “That’s half a day.”

Today large men in blue aprons and yellow gloves hand-rub each of the 17- to 26-pound hams with a mixture of sugar and flake salt and stack them in stainless steel vats to cure for a month. Then they’re lifted out, rinsed, rubbed with pepper and wrapped in nets before being moved to the winter room, which is kept at 40 degrees and a chilly 80 percent humidity, where they’ll stay for another month. Sam walks from there to the 50-degree spring room, the smell green and meaty, where the hams will hang for two or three weeks to cure. Over the course of their last three days there the temperature around them will be raised to 85 degrees, while workers light damp hickory sawdust – a process they call “stoking the smokes” – and fill the smokehouse with smoke so thick you can’t see your hand at the end of your arm. The hams will spend most of a week in there, developing a dark mahogany color before they’re moved into the earthy-smelling summer room that’s kept at a steady 85 degrees. Some will stay only four months, some four years, Sam smelling and tasting, checking temperatures and humidity on his smartphone from the dinner table, the bedside table.

In all, Edwards will process 55,000 hams this year, plus sausage and bacon.

Sam changed suppliers, searching out those that kept at least some of the fat. About 80 percent of Edwards hams and bacon are still made from those so-called pink pigs, but at around the same time, Sam connected with Patrick Martins, the founder of Heritage Foods USA, who delivers 200 green hams a week from pasture-raised, antibiotic-free heritage breed pigs. Red Wattles, Berkshires, Tamworths and Large Blacks, even the occasional Mangalitsa, a Hungarian pig with the long woolly hair of a sheep and so much fat that it makes an excellent long-cured ham.

Among Sam’s recent innovations: the prized Surryano ham, made from Berkshires raised at the Seward farm nearby. :: Photography by Adam Ewing

The making of such delicacies is as much an art as a science. Weather changes. So do pigs. In the 1990s, when customers insisted that meat be lean and the airwaves were overrun with ads for The Other White Meat, pig farmers changed their stock to commodity pigs, raised on concrete floors and fed grain, and artificially bred to be lean. The meat got paler, there was no fat on the outside, the marbling nearly disappeared and it became harder to make a good Virginia ham.

Up the road at Red Barn Berkshires, Berkshire pigs run through the woods, raised specifically for Edwards. For the last three months of their lives farmer Tony Seward supplements their feed with No. 2 peanuts – the small ones that don’t make it into ballpark bags – which makes their meat rich and smooth and suitable for Edwards’ newest signature product, the Surryano ham, aged from 18 months to four years and so buttery and delicious it’s used by chefs across the country. The name is a play on Serrano ham, the expensive Spanish ham made from acorn-fed pigs. It melts on the tongue; the flavor lingers.

“The oil from the peanuts gives the ham a unique flavor and texture – you get moist, satiny, rich, buttery and sweet tastes to the tongue instead of the burn of salt,” says Edwards sales manager Keith Roberts.

Roberts is a ham evangelist, traveling to food shows, appearing in promotional videos and talking directly with at least 40 James Beard chefs who work with Edwards hams.

One of them is Linton Hopkins, owner of Restaurant Eugene and other famed Atlanta eateries.

“I simply love the peanut-fed ham,” he says. “I love what it does to the taste,

texture, fat, marbling, amino acid crystallization. … It’s wonderful to shave it by hand, and people try it and say in a Spanish accent, ‘This is a beautiful jamón,’ and I tell them, no, this is a country ham from Virginia.”

The Surryano graces the menu in his restaurant and at food shows, where he

enjoys the drama of slicing it straight off the shank. He likes the sweetness, the nuttiness, the balance of what he calls “this beautiful artisan product.”

“I’m so proud of that ham,” he says.

The secret is in the combination of peanuts and heritage pigs that are allowed to run and root, and reproduce naturally. They’re far more expensive, but they’re also far more flavorful, Edwards says.

“That took a big investment, but he knows that 50 years from now that will have been a good business decision,” says Martins from Heritage Foods. “There are a lot of people in Sam’s position who don’t think about 50 or 100 years down the line, but Edwards is already 88 years into the business; by the nature of that he thinks about what happens in the future.”

Edwards gets other pigs from farms in the Midwest, which he visits to make sure the animals are well treated. “We feel like if the hog is not under stress the meat comes out tasting and looking better.”

One farm had nose rings on the hogs, to keep them from rooting.

“But happy pigs like to root,” Sam III says, “and happy animals make better meat.”

So he stopped buying from that farm.

“You can tell if farmer’s good at raising hogs,” he continues. “If you pull up and come to the fence and they come running to you, that’s a good sign. If they go the other way they’re afraid of humans, and that’s not a good thing. On Tony’s farm, if he’s in the pen and walking toward them they’re practically like dogs jumping up on him.”

Edwards is also known for its sausage and bacon, giant slabs of it, which hang for 24 hours in cool, 120-degree smoke. If they’re dark enough the next day, they’re pulled out and sliced into strips or wrapped to sell as a slab. “We use real smoke, which gives us real taste,” Roberts says. “We focus on the way it was done hundreds of years ago and stick with it.”

The holidays are their busiest time, just as they were in Grandma Oneita’s day. The company does 70 percent of its business between Thanksgiving and Christmas. There’s another blip around Father’s Day, less so Mother’s Day.

“Smoked meat is for guys, apparently,” Sam says.

“I’d rather get bacon than a tie any day,” Roberts says.

Back in the 1990s, Sam had shouldered a Betamax video recorder and filmed his mother’s demonstration of how to cook a Virginia ham. The kitchen is small and homey, the speech unscripted. A phone rings in the middle of the shoot and grandfather Wallace makes a cameo appearance in a white shirt and tie to show the right way to carve the correctly thin slices.

The era was pre-social media. Now Roberts and Sam IV – called Sammy by the family – cut and edit video, showing chefs and customers how to carve, how to barbecue, how to take ham and bacon beyond breakfast. Sammy, 25, who grew up rollerblading through the plant, takes packages of maple bacon back to his roommates and out to tailgate parties, and vacuum-sealed ham steaks on camping trips. He and his sister, Stephanie, 26, who has a business degree in medical administration, may someday run the company.

By then, if things work as Sam plans, they’ll be using even more heritage meat, both because of the flavor and because the easiest way to preserve genetic diversity in the pig world is to create demand for pigs that are different, and without genetic diversity there’s a risk that entire porcine populations could someday be wiped out by a pathogen. The National Pork Board thinks what Heritage Foods is doing is a fad, Sam says. “They look at me and say it’s all about marketing, but the heritage pork just tastes better. I wouldn’t buy it if it didn’t.”

The heritage pigs and his long years of hands-on ham making allow Edwards to create a ham that’s much like those made by his grandfather, the kind that made Virginia ham famous. He has the touch.

Or as his late father said: “You know what makes a good ham and you just maintain the standard, not deviate from it. You pay attention to detail. Times change and you have to keep changing with it, but once you know what’s right you just adhere to it.”

Originally published in DISTINCTION, November 15, 2014